Simˈpōzēəm

The following White Paper was prepared by Christian Laux at the Center for Financial Studies for a “Workshop on Liquidity Premium in Solvency II: Conceptual and Measurement Issues,” at DNB Amsterdam in March 2011. Although the proposal to introduce a “liquidity premium” in Solvency II has been updated, the discussion of the concept of a liquidity premium and the subsequent comparison to the banking sectors in the comment is still instructive for the debate. The paper is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author, Christian Laux, Vienna University of Economics and Business & Center for Financial Studies (CFS) — Prepared for the “Workshop on Liquidity Premium in Solvency II: Conceptual and Measurement Issues,” DNB Amsterdam, March 18, 2011.The insurance industry and the Committee of European Insurance and Occupational Pension Supervisors (CEIOPS) propose to add a liquidity premium to the risk-free rate when discounting liabilities in times of financial turmoil. The objective is to counterbalance adverse effects on regulatory capital due to a decrease in asset values caused by illiquidity in a crisis. As I argue in this note, although the motive might be sensible, the proposal to add a liquidity premium when discounting liabilities is not the right approach to tackle the problem.

Setting

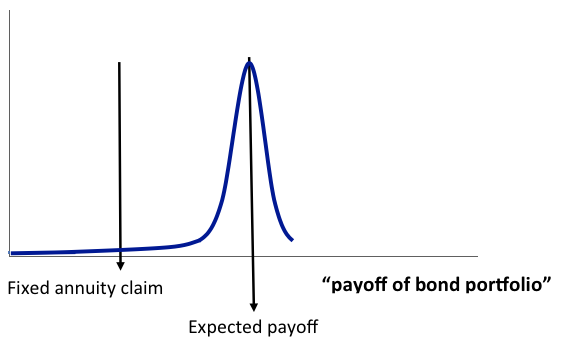

Insurers invest insurance premiums and risk capital in assets to cover policyholders’ claims. Regulation and prudence requires insurers to assure that they can repay the claims at least with probability q. Assume that the insurer sold a fixed annuity policy and holds illiquid corporate bonds with the same maturity as the fixed annuity claim. The corporate bonds may default, but the level of investment is chosen so that the insurer is solvent with probability q.

Now, assume that there is a liquidity shock. Because of the liquidity shock the value of the insurer’s assets decreases. However, to separate the issue of changes in the liquidity premium from changes in credit risk, I assume that the bonds’ default risk does not change. Of course, in practice, this assumption is not satisfied, and it will be difficult to disentangle the effects of changes in liquidity, risk premiums, and credit risk on asset values. But this problem is well known. The focus of this note is how to deal with a liquidity shock (assuming it can be identified); this question in itself is interesting and challenging.

Assume that the insurer sold a fixed annuity policy and holds illiquid corporate bonds with the same maturity as the fixed annuity claim. The corporate bonds may default, but the level of investment is chosen so that the insurer is solvent with probability q.

Now, assume that there is a liquidity shock. Because of the liquidity shock the value of the insurer’s assets decreases. However, to separate the issue of changes in the liquidity premium from changes in credit risk, I assume that the bonds’ default risk does not change. Of course, in practice, this assumption is not satisfied, and it will be difficult to disentangle the effects of changes in liquidity, risk premiums, and credit risk on asset values. But this problem is well known. The focus of this note is how to deal with a liquidity shock (assuming it can be identified); this question in itself is interesting and challenging.

The case for a liquidity premium (based on CEIOPS Task Force Report on the Liquidity Premium):

- Because the maturities of the bonds and the claims of the policyholders are matched, the insurer can hold the assets until maturity to cover the policyholders’ claims. Indeed, the picture above does not change and the liquidity shock and the corresponding decrease in asset values do not affect the solvency of the insurer. However, if the decrease in asset values is reported as a loss in the income statement, it decreases the insurer’s equity and thus regulatory capital if no adjustments are made.

- To avoid the negative effect on regulatory capital, which, in the underlying scenario, can be misleading and contribute to procyclicality in a crisis, it is proposed to also discount liabilities with a higher liquidity premium in a crisis. The adjustment of the discount rate by a liquidity premium reduces the present value of liabilities and the corresponding gain offsets the decrease due to the loss on the asset side.

Recommendations:

Regulators might be concerned that a liquidity shock can reduce regulatory capital even when solvency is not affected (as in the stylized case above). This could increase insurers’ cost of selling long term insurance policies and, more critically, contribute to procyclicality. However, in this case, regulators should deal with this problem directly by not deducting the corresponding value change from regulatory capital or by introducing countercyclical capital buffers. Both alternatives are more transparent and reduce the risk of potential mistakes (Although a liquidity premium for liabilities could, in theory, be designed to achieve the same effect, the approach is indirect and artificial). For example, if the accounting treatment of (unrealized) losses of asset values (due to a liquidity shock) reduces equity, it can be added back to regulatory capital. A similar approach is followed in banking regulation in many countries, including the U.S., where unrealized losses of available for sale debt securities (which are reported in other comprehensive income) are added back to regulatory capital. However, regulators have to carefully consider whether maturities are indeed matched and whether a liquidity shock really does not affect solvency. In the current crisis, many financial institutions encountered problems not because of regulatory capital problems, but because of refinancing problems, which were affected by the liquidity shock.A look at banks

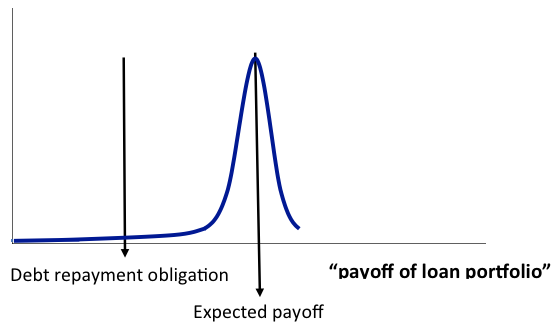

Assume that a bank grants loans (or holds a bond portfolio) with a face value of B. The loan repayment R is uncertain and the bank needs the amount B to finance the loan portfolio. How much debt can the bank use to finance the loan portfolio if the bank should be solvent with probability q? The maximum debt repayment obligation D is chosen such that Pr(R < D) = 1–q, and the required equity to finance the loan portfolio is B–PV(D). Thus, for a given debt repayment obligation, the required equity increases in the risk of default 1–q and the illiquidity of the liability claim (e.g., if a more opaque bank issues a bond).

How should regulators deal with changes in

The maximum debt repayment obligation D is chosen such that Pr(R < D) = 1–q, and the required equity to finance the loan portfolio is B–PV(D). Thus, for a given debt repayment obligation, the required equity increases in the risk of default 1–q and the illiquidity of the liability claim (e.g., if a more opaque bank issues a bond).

How should regulators deal with changes in

- Credit risk of assets (and its impact on the risk of outstanding liabilities)

- Liquidity of assets

- Liquidity of liabilities