Simˈpōzēəm

Paul Fulcher, European Head of ALM Solutions at Nomura

Regulation must adapt to market developments. The long delays in implementing Solvency II resulted in an inevitable need to update the rules. But Paul Fulcher, European Head of ALM Solutions at Nomura, argues that the original commitment to value-at-risk and counter-cyclicality are contradictory and have produced the complex mess we now know as the Long-term Guarantees package.

Traditionally, insurance regulation has focused on the long-term ability of insurers to meet claims as they fall due. The challenge for regulators has always been how to monitor this ability at intermediate points to ensure timely intervention. Under the current (“Solvency I”) regimes across Europe this is typically a retrospective assessment, without explicit reference to market data and a reliance on techniques such as book values, asset-based discounting, implicit margins and actuarial judgement.

Solvency II, in its purest form, changes this by introducing a market-consistent valuation of assets and liabilities and a risk-sensitive capital requirement calibrated to a one year 99.5% VAR. Existing techniques are replaced by market prices, exogenous “risk-free” rates, explicit capital, and objective data.

Solvency II is overhauling many established processes and in assessing its impact it is important to bear in mind that regulation is ultimately about political objectives rather than being an exact science.

The key political rationale behind the original directive was to introduce a harmonised, modern, risk-based and prospective assessment of solvency. But insurers cannot be risk-free unless capital is infinite. And the level of acceptable risk is also political. In particular, there is nothing sacred about a 99.5% confidence level assessed over a one year horizon. Different confidence intervals and different assessment periods – including run-off – could have equally met this political rationale.

Paul Fulcher, European Head of ALM Solutions at Nomura

Regulation must adapt to market developments. The long delays in implementing Solvency II resulted in an inevitable need to update the rules. But Paul Fulcher, European Head of ALM Solutions at Nomura, argues that the original commitment to value-at-risk and counter-cyclicality are contradictory and have produced the complex mess we now know as the Long-term Guarantees package.

Traditionally, insurance regulation has focused on the long-term ability of insurers to meet claims as they fall due. The challenge for regulators has always been how to monitor this ability at intermediate points to ensure timely intervention. Under the current (“Solvency I”) regimes across Europe this is typically a retrospective assessment, without explicit reference to market data and a reliance on techniques such as book values, asset-based discounting, implicit margins and actuarial judgement.

Solvency II, in its purest form, changes this by introducing a market-consistent valuation of assets and liabilities and a risk-sensitive capital requirement calibrated to a one year 99.5% VAR. Existing techniques are replaced by market prices, exogenous “risk-free” rates, explicit capital, and objective data.

Solvency II is overhauling many established processes and in assessing its impact it is important to bear in mind that regulation is ultimately about political objectives rather than being an exact science.

The key political rationale behind the original directive was to introduce a harmonised, modern, risk-based and prospective assessment of solvency. But insurers cannot be risk-free unless capital is infinite. And the level of acceptable risk is also political. In particular, there is nothing sacred about a 99.5% confidence level assessed over a one year horizon. Different confidence intervals and different assessment periods – including run-off – could have equally met this political rationale.

Conflicting objectives in Solvency II

Quite simply, the regulatory objectives at the heart of Solvency II are in conflict. The directive requires that Solvency II mitigates undue pro-cyclical effects on financial markets. Yet pro-cyclicality is inevitable if a value-at-risk based approach is applied consistently to an industry that makes up a significant part of the European investment landscape. A one-year value-at-risk approach became hard-coded into the Solvency II directive from an early stage, and this decision is at the heart of many of the problems that have resulted. Avoiding pro-cyclicality is also incompatible with a fixed risk objective. Historically, regulators have tended to massage capital requirements in times of stress. Examples include the relaxations to the UK resilience test in 2001-3 or the more recent changes to discount rates in Sweden, Denmark and The Netherlands.Long-term finance and Solvency II: added confusion

In response to the crisis, the European Commission recently added an important new objective. It tasked EIOPA with ensuring that Solvency II would allow insurers to provide long-term finance to support the economic recovery in Europe. While this is a commendable goal, it is compounding the already conflicted objectives. The value-at-risk approach requires an insurer to hold capital against the risk of liquidation at the worst possible time. They must be capitalised to withstand a once-in-200-year extreme market event, and still have sufficient proceeds from selling assets at distressed prices to invest in “risk-free” assets, inevitably trading at elevated prices, sufficient to defease liabilities. This short-term approach is in direct conflict with a long-term approach to investment.

Unfortunately, Solvency II was designed during a period of unusually benign markets and the implications were originally not well understood. The industry’s own impact assessment, published by the CEA in March 2007, reported that, “The majority of respondents expect no changes or only limited changes in their investment strategies”. The only exception noted was for equity investments, particularly by French insurers, and this led directly to the introduction of an equity “dampener” – the first fudge to the pure Solvency II approach.

Roll the clock forward six years to March 2013 and the very same body, renamed Insurance Europe, now argues that, “Not addressing the issues of artificial volatility and pro-cyclicality risks insurers shifting from longer-term to shorter-term assets, limiting the insurance industry’s traditional role of investing in and assisting growth in the European economy.”

So how can insurers provide long-term finance under Solvency II? They need to be able to withstand losses from market fluctuations without being forced into fires sales of assets. Their ability to do this requires a combination of different actions.

Firstly, insurers need to hold sufficient buffer capital. For example, peripheral government bonds might be capital free under the standard formula SCR but a large capital buffer would still be needed to withstand market volatility. Associated with this, insurers may look to transfer risk to the capital markets via derivative hedges, which provide a form of contingent buffer capital.

In addition, insurers will need to diversify into assets that perform well during times of stress. Insurers may be able to pass losses on to policyholders, in unit linked or participating business, or look to offset market value fluctuations in reduced technical provisions or capital requirements.

The value-at-risk approach requires an insurer to hold capital against the risk of liquidation at the worst possible time. They must be capitalised to withstand a once-in-200-year extreme market event, and still have sufficient proceeds from selling assets at distressed prices to invest in “risk-free” assets, inevitably trading at elevated prices, sufficient to defease liabilities. This short-term approach is in direct conflict with a long-term approach to investment.

Unfortunately, Solvency II was designed during a period of unusually benign markets and the implications were originally not well understood. The industry’s own impact assessment, published by the CEA in March 2007, reported that, “The majority of respondents expect no changes or only limited changes in their investment strategies”. The only exception noted was for equity investments, particularly by French insurers, and this led directly to the introduction of an equity “dampener” – the first fudge to the pure Solvency II approach.

Roll the clock forward six years to March 2013 and the very same body, renamed Insurance Europe, now argues that, “Not addressing the issues of artificial volatility and pro-cyclicality risks insurers shifting from longer-term to shorter-term assets, limiting the insurance industry’s traditional role of investing in and assisting growth in the European economy.”

So how can insurers provide long-term finance under Solvency II? They need to be able to withstand losses from market fluctuations without being forced into fires sales of assets. Their ability to do this requires a combination of different actions.

Firstly, insurers need to hold sufficient buffer capital. For example, peripheral government bonds might be capital free under the standard formula SCR but a large capital buffer would still be needed to withstand market volatility. Associated with this, insurers may look to transfer risk to the capital markets via derivative hedges, which provide a form of contingent buffer capital.

In addition, insurers will need to diversify into assets that perform well during times of stress. Insurers may be able to pass losses on to policyholders, in unit linked or participating business, or look to offset market value fluctuations in reduced technical provisions or capital requirements.

LTG package a complex mess

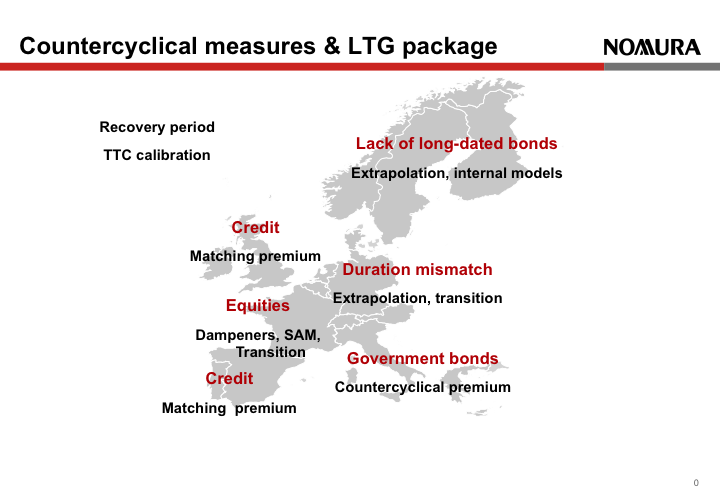

[caption id="attachment_78587" align="alignright" width="432"] Countercyclical measures & LTG package by region SOURCE: Nomura[/caption]

This leads us to the Long-term Guarantees (LTG) package. Under the current regime, insurers across Europe have typically regarded particular assets as a good match for long-term liabilities. In practice, this has meant holding corporate bonds in the UK and Spain, while French and Portuguese insurers prefer equities. Italian insurers have favoured domestic government bonds whereas a dearth of long-term bonds in Scandinavia has lead to a focus on infrastructure and property in Scandinavia. In Germany a strategy of deliberate duration mismatch has been adopted when long-term yield curves are inverted.

Fixing the rules to meet each country’s legacy requirements – while maintaining the façade of an EU-wide and consistent system of value-at-risk based regulation – has produced the complex mess we know as the Long Term Guarantees package. It is the wrong way to approach the problem.

I am strongly supportive of the idea that Solvency II should reflect wider political objectives. Yet while the LTG package attempts to achieve this, I take issue with the complex pseudo-science involved; seemingly seeking a magic theoretically correct answer. For example, a fixed (or rising) ultimate-forward rate may be a theoretical feature of an arbitrage-free interest rate model, but this is reached at infinity, not after 20 years.

Measurement of proper market consistent values of assets and liabilities is a valuable tool. The problem arises in the way regulators and other stakeholders react to this disclosure – such as potentially forcing insurers to sell assets at distressed prices during a period of severe market stress.

A value-at-risk approach to capital is only one possible technique and should not have been set in stone in the directive. Given the changing political objectives, a run-off approach may be more appropriate.

However, manipulating the true picture by theoretical fudges, while pretending that regulation is still based on market consistent value-at-risk, is not the answer. Regulation should instead focus on transparent and targeted approaches – for example on treatment of certain long-dated finance assets – with explicit political objectives.

—

The author is European Head of ALM Solutions at Nomura. The views expressed are the author’s own.]]>

Countercyclical measures & LTG package by region SOURCE: Nomura[/caption]

This leads us to the Long-term Guarantees (LTG) package. Under the current regime, insurers across Europe have typically regarded particular assets as a good match for long-term liabilities. In practice, this has meant holding corporate bonds in the UK and Spain, while French and Portuguese insurers prefer equities. Italian insurers have favoured domestic government bonds whereas a dearth of long-term bonds in Scandinavia has lead to a focus on infrastructure and property in Scandinavia. In Germany a strategy of deliberate duration mismatch has been adopted when long-term yield curves are inverted.

Fixing the rules to meet each country’s legacy requirements – while maintaining the façade of an EU-wide and consistent system of value-at-risk based regulation – has produced the complex mess we know as the Long Term Guarantees package. It is the wrong way to approach the problem.

I am strongly supportive of the idea that Solvency II should reflect wider political objectives. Yet while the LTG package attempts to achieve this, I take issue with the complex pseudo-science involved; seemingly seeking a magic theoretically correct answer. For example, a fixed (or rising) ultimate-forward rate may be a theoretical feature of an arbitrage-free interest rate model, but this is reached at infinity, not after 20 years.

Measurement of proper market consistent values of assets and liabilities is a valuable tool. The problem arises in the way regulators and other stakeholders react to this disclosure – such as potentially forcing insurers to sell assets at distressed prices during a period of severe market stress.

A value-at-risk approach to capital is only one possible technique and should not have been set in stone in the directive. Given the changing political objectives, a run-off approach may be more appropriate.

However, manipulating the true picture by theoretical fudges, while pretending that regulation is still based on market consistent value-at-risk, is not the answer. Regulation should instead focus on transparent and targeted approaches – for example on treatment of certain long-dated finance assets – with explicit political objectives.

—

The author is European Head of ALM Solutions at Nomura. The views expressed are the author’s own.]]>

Excellent article with which I generally agree. I do think the eurozone difficulties and the continuing lack of mutual confidence in the management of the single currency are major contributory factors to the mess in which we find ourselves. I personally would have preferred that the Commission and EIOPA would have adopted a much more flexible approach to transition for legacy business.

Thanks Seamus. Yes the eurozone difficulties are a major factor – and make a one-size-fits-all approach difficult. For example the issues faced by German insurers with long-term guarantees (ultra-low long-duration yields) are rather different from those in the periphery (high sovereign spreads). Indeed, to be fair to everyone involved, the Solvency II process was rather unlucky with its timing as the system was designed in the pre-financial-crisis “Goldilocks economy” of stable markets – unfortunately as we know Goldilocks turned out to be a fairy tale. E.g. the CEA paper I refer to that said Solvency II would have only minor, and benign, impacts was released in March 2007, just as the subprime crisis was starting to become a concern.

Some more thoughts on the Pillar 1 problem – comments welcome!

There are at least two separate issues – valuation and capital requirements.

In relation to valuation, measuring the fair or market-consistent values of both assets and liabilities is at least very useful information for stakeholders. There is solid and to best of my knowledge generally uncontroversial guidance as to how to measure fair or market-consistent values for assets, including guidance on discounts for illiquidity. (An exception may be measurement of fair values of sovereign and similar bond assets within the euro countries). Actuaries have developed techniques for measurement of fair or market-consistent valuation of liabilities, but there is a lack of consensus on recognition of the liquidity characteristics of liabilities. If one interprets fair or market-consistent value as corresponding to the amount which would pass between two willing parties exchanging liabilities, then it is easy to establish that an illiquid liability has a lesser value than an otherwise similar liquid liability but very difficult to establish by how much. Replication arguments used by proponents of the ‘illiquidity premium’ are not necessarily convincing. This is not to suggest that fair value is the only possible balance sheet basis, and there are good arguments for the net effects of movements in fair values not to go through P&L. Measuring the balance sheet on fair value concepts does not of itself introduce asset bias.

However own funds measured on a fair value basis, even properly taking into account liquidity characteristics of liabilities as well as of assets, will be volatile because of cyclical and other market influences. This poses the challenge of how to flex capital and solvency standards so that the volatility does not become destabilising. At a minimum it seems likely that the 99.5{fe5cadadbb54208ab3a9fe6506ec07abb84961fe5f7860e6b90ac4d8e68f73da} confidence requirement should be able to be flexed ‘through the cycle’ – higher when markets are at their most buoyant and lower when they are weak. While such flexibility is desirable, it may well not be enough to deal with all sets of foreseeable circumstances. It certainly is desirable that other contracyclical tools are available, such as the power to lengthen recovery periods. I think I can see that it may be desirable to retain additional flexibility in relation to movements in longer-term asset and liability values as compared with movements in shorter-term values.

Thanks for the article Paul – quite a useful read. I hadn’t realised the extent to which different parts of Europe had been entrenched in different ‘optimal’ investment strategies.

If there was one unifying political objective that favours a particular asset class – I would have thought (especially in current times), that it perhaps ought to be infrastructure.

Thanks Parit. Yes, another issue with Solvency II is that reconciling the objectives of a one-size-fits-all common regime with limiting disruption to existing business models is very difficult when the starting points of different countries are so different. I would agree with your comment on infrastructure and indeed the recent Green Paper on long-term investment was focused on this point. However, the current LTG package doesn’t appear to offer any solutions and indeed some aspects – e.g. the strict limits on matching premium eligiblity – could make infrastructure investment even more difficult. Treatment of infrastructure has been raised before – e.g. during the QIS5 process – but EIOPA have previously declined to provide any special treatment and have instead suggested use of internal models.

Further to Parit’s comments, EIOPA have responded to the Commission’s request and today published their preliminary proposals on the treatment of long-term investments such as infrastructure. But disappointingly their analysis appears to have been purely technical – based on evidence of actual market volatility which is lacking in many cases – and hence their conclusion is that no changes are warranted to the Standard Formula treatment of such assets. What they appear to have ignored is the political policy angle – i.e. what sort of behaviour Solvency II is designed to encourage.