We are living in a turbulent and ever-changing world, flooded by multiple and ongoing emerging threats and risks. To manage this risky terrain, Catherine Drummond, Partner at LCP, argues that insurers do not need to be crystal-ball-gazers, but rather gain a clear understanding of how and where they fit into the picture.

The rocky geopolitical terrain

Geopolitical risk is shaping the operating environment for insurers in ways that are more visible, more complex and more urgent than many are used to managing. Physical conflict, economic sanctions, regime instability, and political fragmentation are just some of the forces disrupting markets. These risks are amplified by the growing interconnectedness of global systems, which makes it harder to contain or isolate the effects of any single event.

But faced with such a challenging environment, insurers do not need to precisely predict the next crisis in order to manage these risks. Instead, they should map clearly the global dynamics affecting the major territories and lines of business they are exposed to and then explore a range of plausible (and less plausible) events that could affect them.

Mapping exposure through trade routes

Consider a hypothetical UK-based non-life insurer. To understand how geopolitical developments might affect its business, it helps to trace the flow of goods between Asia and Europe, which is a critical artery for global trade and the wider economy on which many insureds depend.

Goods by air and sea

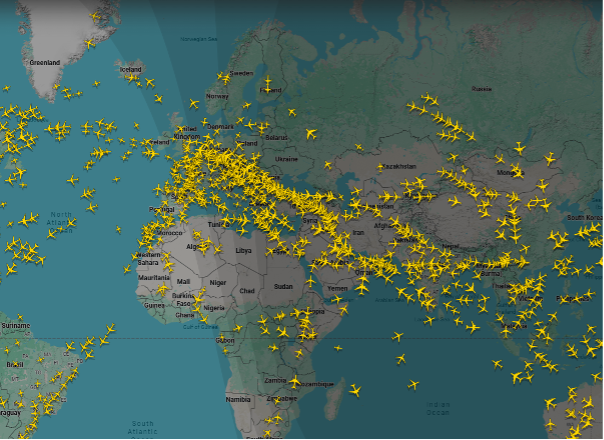

Most goods reach the UK either by air or sea. Air freight typically crosses routes through the Middle East.

As can be seen in the flightradar image below, these routes pass through the airspace over Iraq and Turkey, or over Central Asia and China.

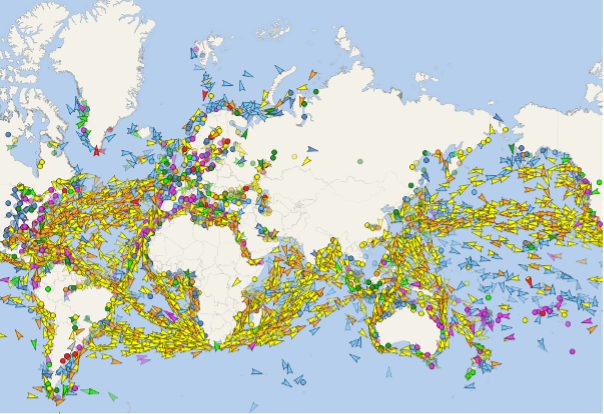

Maritime shipping (which carries the vast majority of goods) typically passes through the Suez Canal, with some vessels rerouting around the Cape of Good Hope when disruptions occur.

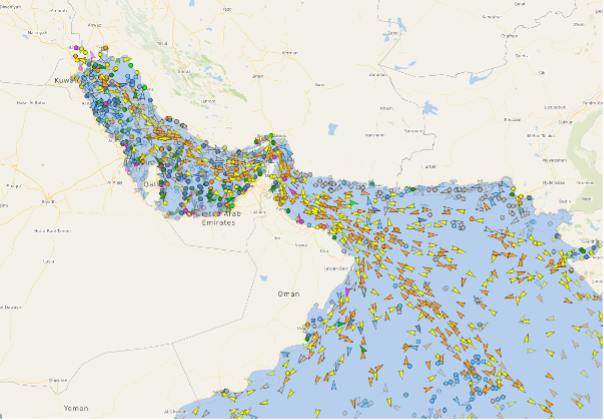

This snapshot from VesselFinder shows the current position of vessels across the world.

Oily routes

Another key artery affecting the region is the Strait of Hormuz, which is located in a narrow corridor within the Persian Gulf. While not a direct part of this Europe – Asia corridor, it is strategically significant as a vital route for global oil and gas exports.

The following image from VesselFinder shows the volume of shipping traffic in the area.

Mapping geopolitical risk

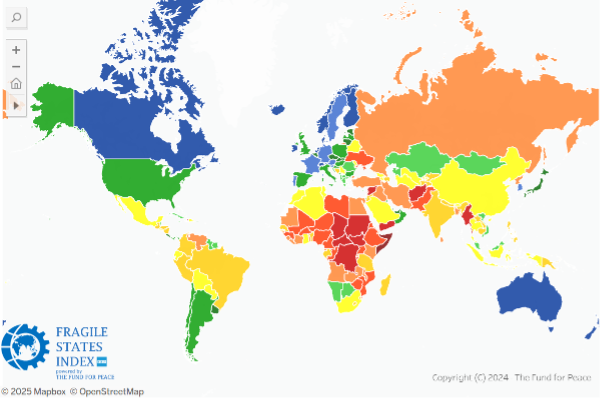

One way of assessing the risk of disruption to any of these vital arteries for the European economy is to overlay them on a map of political instability of the regions they cover.

The map below is taken from Fragile States Index, which maps political instability across the globe, showing those countries that may be most at risk of future conflict or volatility.

Considering these cargo and shipping channels in the context of political instability reveals that these commercially important routes traverse some of the most geopolitically volatile areas in the world today.

Disruption at any of these points could ripple across supply chains, trade flows, and insurers’ underwriting, investment operational exposures.

Painting the full picture

This type of analysis can serve as a solid basis for some basic scenario planning. Consider a few plausible examples that could disrupt, or have already disrupted, these routes.

The ongoing conflict in the Middle East has escalated and involved military action in Israel, Iran and Yemen, over the past two years.

Attacks by Houthi rebels in the Red Sea have diverted commercial vessels from the Suez Canal, a key artery linking Europe and Asia.

This, for example, is already having an impact, as many are now travelling the longer and more expensive route around the Cape of Good Hope. To counter this shift, earlier this year the Suez Canal Authority introduced toll discounts, but traffic remains well below normal levels.

In the Gulf, Iran has raised the possibility of closing the Strait of Hormuz, which is a vital trade route for oil and gas exports. While no formal action has been taken, the risk of escalation remains.

At the same time, reports of GPS interference and cyber threats affecting navigation systems in several regions have heightened concerns about the vulnerability of critical infrastructure. Any escalation there could indirectly affect energy prices, shipping costs, and broader market stability; all of which have implications for insurers’ risk profiles.

Disruption to major trade routes could lead to a surge in claims across multiple lines of business including marine, aviation, business interruption, political risk and credit. Investment portfolios could also be affected by market volatility, particularly in the energy sector.

Going beyond the plausible

But it’s also important to go beyond the plausible. Including more extreme or unexpected scenarios can highlight areas of exposure that may not be sufficiently captured through standard modelling. This is particularly useful when assessing the resilience of the business to rare but disruptive events that fall outside historical experience.

For example, consider the coordinated sabotage of key port infrastructure across multiple continents, or a large-scale state-sponsored disinformation campaign triggering widespread panic and operational disruption.

Scenarios like these can help test assumptions about dependencies, accumulations and operational resilience and prompt important questions about whether the business is prepared.

Risks beyond the trade routes

The implications of geopolitical risk go beyond just disrupted trade routes. Cyber threats are escalating, with attacks on infrastructure and navigation systems becoming more frequent.

Terrorism risk, both state-sponsored and independent, remains a constant concern in politically unstable regions.

And fragile economies, particularly those with high sovereign debt or reliance on key exports, may face heightened default risks and credit downgrades.

These factors can all contribute to further losses and wider financial instability.

From mapping to understanding exposure

While mapping and assessing risks are vital, understanding exposure is just as important.

Insurers should map how their policies connect to global trade networks and supply chains, and identify concentrations in high-risk regions. This may require input from underwriting, exposure management, operations and claims teams.

Is our view of the 1 in 200 still appropriate?

In light of the changing risk landscape insurers should also consider how adequately capital models cover these risks, and to what extent, for example, does the standard formula in Solvency II cover the 1 in 200 risk event.

While short-term fluctuations might not justify a recalibration, sustained or worsening risks could be addressed through additional modelling or expert judgement overlays.

Conclusion

Geopolitical risk is no longer a background concern. For many firms, it is becoming a more visible and material part of the risk profile and deserves more structured and deliberate consideration going forwards.

Insurers do not need to predict every twist in the global landscape to manage their risks. But they do need to stay proactive. Understanding where exposures lie, how they might evolve, and how to reflect them in modelling, planning and decision-making is key to navigating todays rugged and risky global terrain.

—-

Catherine Drummond is a Partner and Insurance Consulting Leader at the consultancy firm LCP. Views expressed are the author’s own.