Simˈpōzēəm

The Solvency II Extrapolation has become a central element of the Long-Term Guarantees package. But what started as a purely technical concept to value ultra long-dated liabilities was hijacked and has become a tool for managing pro-cyclicality.

The Solvency II Extrapolation has become a central element of the Long-Term Guarantees package. But what started as a purely technical concept to value ultra long-dated liabilities was hijacked and has become a tool for managing pro-cyclicality.

Introduction

An economic extrapolation is a method of using known market values to estimate, or ‘extrapolate’, future values for which there is no accurate market data. In Solvency II it is used to smooth market volatility at the long-end of the interest rate curve by providing a more stable regulatory risk-free rate against which insurers’ long-term liabilities can be discounted. Essentially the Solvency II Extrapolation is comprised of three elements: the fixed interest rate to which long-dated forwards are assumed to converge (the Ultimate Forward Rate or UFR); the point from which market data is no longer used (the Last Liquid Point or LLP); and the rate of convergence from market rates at the LLP to the UFR.

Extrapolation has evolved from an obscure market methodology to becoming a ‘best practise’ solution in less than half a decade. Tracing its history we can see that as the discussion became more politicized, the technical debates on improving the method were interrupted. Further, the political debate has focused on the LLP and the convergence rate, with little consideration given to the UFR itself.

Applying the wrong UFR could prove costly. Analysing the UFR in a historical context shows that the current Solvency II methodology leaves insurers exposed to two challenging scenarios: a Japanese style protracted low interest rate period, or conversely, a 1994 style interest rate shock.

Essentially the Solvency II Extrapolation is comprised of three elements: the fixed interest rate to which long-dated forwards are assumed to converge (the Ultimate Forward Rate or UFR); the point from which market data is no longer used (the Last Liquid Point or LLP); and the rate of convergence from market rates at the LLP to the UFR.

Extrapolation has evolved from an obscure market methodology to becoming a ‘best practise’ solution in less than half a decade. Tracing its history we can see that as the discussion became more politicized, the technical debates on improving the method were interrupted. Further, the political debate has focused on the LLP and the convergence rate, with little consideration given to the UFR itself.

Applying the wrong UFR could prove costly. Analysing the UFR in a historical context shows that the current Solvency II methodology leaves insurers exposed to two challenging scenarios: a Japanese style protracted low interest rate period, or conversely, a 1994 style interest rate shock.

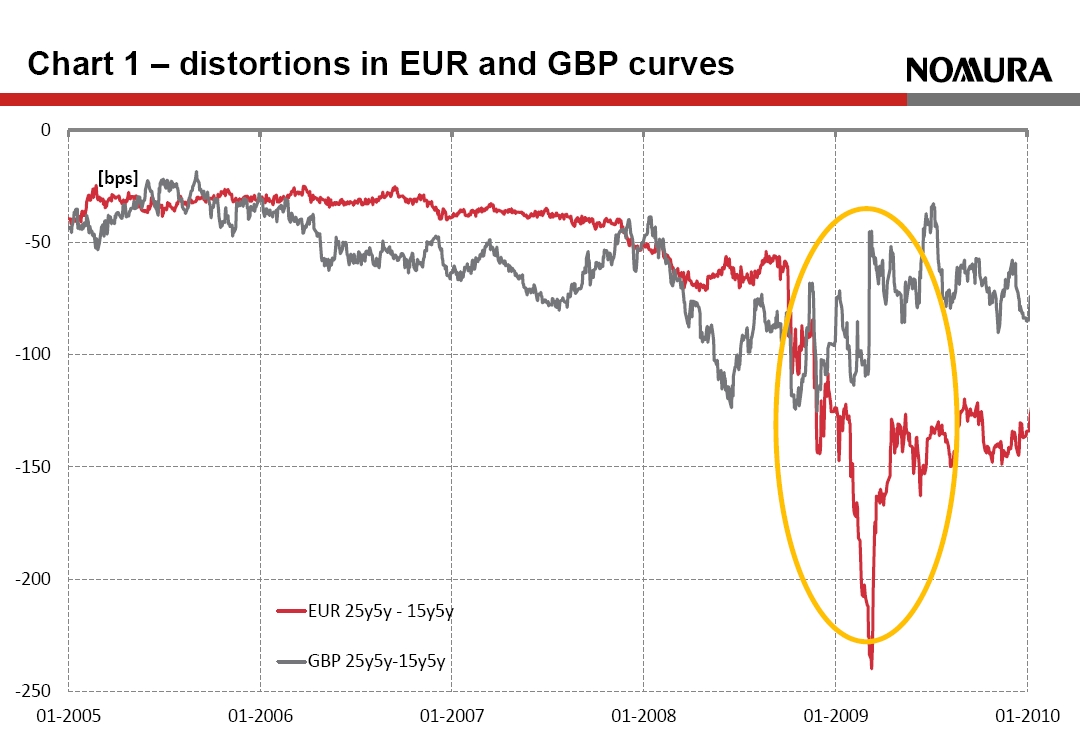

Origins of macro-economic extrapolation

The Solvency II Directive text (Article 76) requires that technical provisions are consistent with market prices and financial market data. Extrapolation was originally proposed only as a theoretical technique to place a market-consistent value on a non-traded item, namely ultra-long-dated cash-flows past the term of any traded instruments, for example after 50 years in Euro (EUR). Following the global financial crisis, stakeholders started to question the reliability of market data and the potential impact of market-consistent valuation on macro-economic stability. Extrapolation was identified as a possible tool to manage pro-cyclicality. [caption id="attachment_119108" align="alignright" width="389"] This chart shows the difference between market forward rates at a 25 year and 15 year maturity for EUR and GBP. In the absence of supply-demand distortions, e.g. caused by regulatory-driven asset-liability hedging, one would expect this difference to be small and positive, and indeed this is the underlying assumption of Solvency II Extrapolation. Actual market rates tell a different story. SOURCE: Nomura[/caption]

During the crisis, markets experienced severe falls in prices of equity and credit assets accompanied by significant falls in long-dated yields. Insurers and pension funds in Europe, particularly in the Netherlands and Scandinavia were already subject to mark-to-market and risk-based capital rules, and as a result came under solvency pressure. They were forced to reduce risk and hedge rates to protect solvency, but this further depressed long-dated rates creating a pro-cyclical effect, as shown on Chart 1.

Interestingly, the same effect was not observed in the UK, where insurers were typically fully hedged and where pension funds face less regulatory pressure.

One of the first firms to publicly adopt extrapolation techniques was Storebrand (a leading provider of life insurance and pensions in the Nordic region); extrapolation was included in its end-of-year 2008 embedded value report. The exact method differs from the Solvency II approach, but its use of extrapolated rather than quoted market rates in an ostensibly “market-consistent” valuation was influential on the Solvency II debate.

This chart shows the difference between market forward rates at a 25 year and 15 year maturity for EUR and GBP. In the absence of supply-demand distortions, e.g. caused by regulatory-driven asset-liability hedging, one would expect this difference to be small and positive, and indeed this is the underlying assumption of Solvency II Extrapolation. Actual market rates tell a different story. SOURCE: Nomura[/caption]

During the crisis, markets experienced severe falls in prices of equity and credit assets accompanied by significant falls in long-dated yields. Insurers and pension funds in Europe, particularly in the Netherlands and Scandinavia were already subject to mark-to-market and risk-based capital rules, and as a result came under solvency pressure. They were forced to reduce risk and hedge rates to protect solvency, but this further depressed long-dated rates creating a pro-cyclical effect, as shown on Chart 1.

Interestingly, the same effect was not observed in the UK, where insurers were typically fully hedged and where pension funds face less regulatory pressure.

One of the first firms to publicly adopt extrapolation techniques was Storebrand (a leading provider of life insurance and pensions in the Nordic region); extrapolation was included in its end-of-year 2008 embedded value report. The exact method differs from the Solvency II approach, but its use of extrapolated rather than quoted market rates in an ostensibly “market-consistent” valuation was influential on the Solvency II debate.

Extrapolation in Solvency II

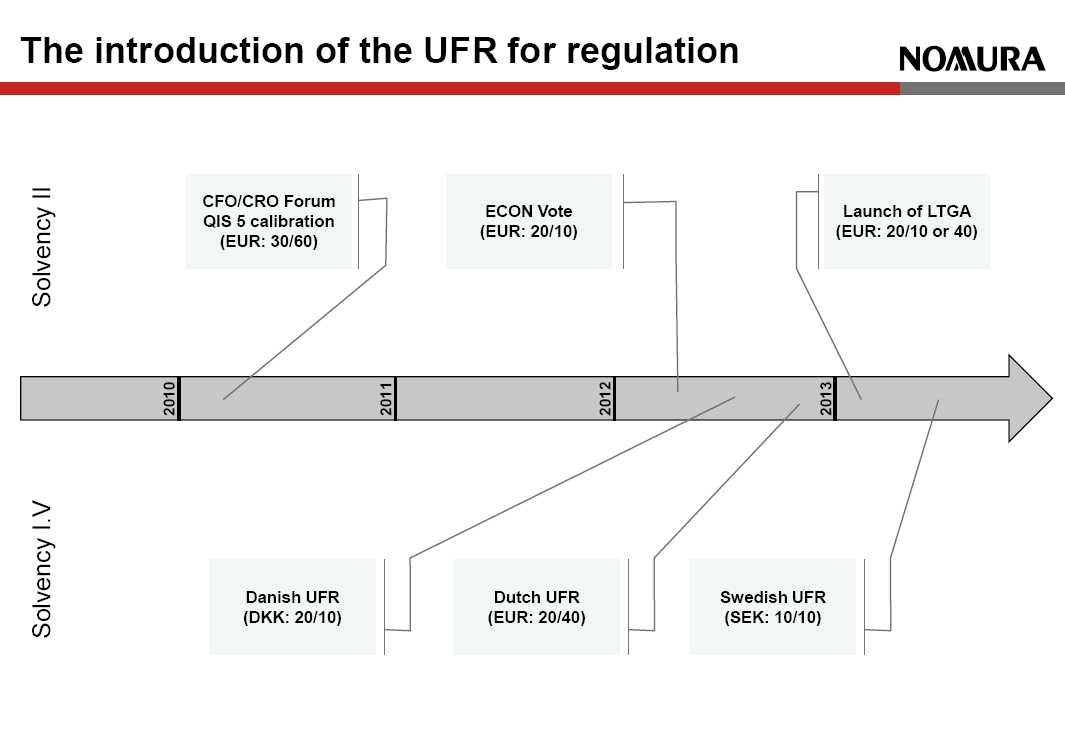

In July 2009 CEIOPS (EIOPA’s predecessor) issued advice on the risk-free rate (Advice from CP40) in which it acknowledged the pro-cyclical effects of volatile long-term rates. It required that, next to a requirement for “realism”, extrapolation techniques should be used to manage the “effect on financial stability”. [caption id="attachment_119113" align="alignright" width="498"] The introduction of the UFR for regulation[/caption]

The extrapolation method currently proposed in Solvency II was born from CEIOPS and industry task-forces who reported in April 2010 (CEIOPS and CFO & CRO Forum).

Looking back on these documents, the only debate about the LLP for EUR was between 30 and 50 years. The industry task force stated, “In liquid times the EUR swap market would be considered somewhat liquid up to a long-term, in a crisis such as end-2008 this would reduce to 30 years”. The extrapolated rates were also intended to only slowly converge to the UFR.

The specific method and calibration proposed was intended only for QIS5, and was to be refined later. For example, CEIOPS Principle #9 stated that further development was expected, “regarding the consideration to be given to observed market data points situated in the extrapolated part of the interest curve.” In other words, modifying extrapolation to reflect observed market values past the LLP. These considerations are ignored entirely in the Solvency II Extrapolation.

CEIOPS’ intention was also that the choice of technique and parameters should be omitted from the Level 1 and Level 2 texts and only be included as a set of principles at Level 3.

The introduction of the UFR for regulation[/caption]

The extrapolation method currently proposed in Solvency II was born from CEIOPS and industry task-forces who reported in April 2010 (CEIOPS and CFO & CRO Forum).

Looking back on these documents, the only debate about the LLP for EUR was between 30 and 50 years. The industry task force stated, “In liquid times the EUR swap market would be considered somewhat liquid up to a long-term, in a crisis such as end-2008 this would reduce to 30 years”. The extrapolated rates were also intended to only slowly converge to the UFR.

The specific method and calibration proposed was intended only for QIS5, and was to be refined later. For example, CEIOPS Principle #9 stated that further development was expected, “regarding the consideration to be given to observed market data points situated in the extrapolated part of the interest curve.” In other words, modifying extrapolation to reflect observed market values past the LLP. These considerations are ignored entirely in the Solvency II Extrapolation.

CEIOPS’ intention was also that the choice of technique and parameters should be omitted from the Level 1 and Level 2 texts and only be included as a set of principles at Level 3.

Finding the Last Liquid Point

At this stage the extrapolation debate was still regarded as technical, albeit with an expanded objective. However, as I previously observed, over time the Solvency II debate became increasingly political. The industry, particularly in Germany, pushed for a shorter-dated LLP – ideally 10 years – and much quicker convergence. [caption id="attachment_119110" align="alignleft" width="233"] Chart 2 What’s specail about 20 years[/caption]

The 20 year LLP that emerged from the ECON Committee in March 2012 was a pure compromise with no technical justification and, I suspect, simply an average of the competing 10 year and 30 year proposals. As Chart 2 shows, volumes and liquidity in the bond and swap markets do drop rapidly beyond 10 years, but then stay at a fairly fixed level until the 30 year tenor.

Extrapolation was seen as so important that in order to reach a compromise the specific method – and for EUR even the parameters underlying the extrapolation – are now being hard-coded into the proposed Omnibus II Level 1 Directive text.

Chart 2 What’s specail about 20 years[/caption]

The 20 year LLP that emerged from the ECON Committee in March 2012 was a pure compromise with no technical justification and, I suspect, simply an average of the competing 10 year and 30 year proposals. As Chart 2 shows, volumes and liquidity in the bond and swap markets do drop rapidly beyond 10 years, but then stay at a fairly fixed level until the 30 year tenor.

Extrapolation was seen as so important that in order to reach a compromise the specific method – and for EUR even the parameters underlying the extrapolation – are now being hard-coded into the proposed Omnibus II Level 1 Directive text.

Convergence of extrapolation techniques

As interest rates on core European government bonds fell further during the sovereign debt crisis, the Dutch, Danish and, most recently, Swedish regulators all adopted Extrapolation for current Solvency I reporting purposes. Inspired by this regulatory endorsement, insurers have used the UFR for the calculation of MCEV, where it has been adopted by more than half of listed insurers. The Smith-Wilson technique and the parameters proposed for Solvency II are also being widely adopted as generally accepted, if not necessarily best, practice. The market impact of adopting these methods has so far mainly been to simply transfer pro-cyclical distortions on the curve from the ultra-long end to around the key 20 year entry point – as noted above this is a relatively artificial choice of tenor. Interestingly the Swedish and Dutch regulators have both recently challenged aspects of the Solvency II Extrapolation, including in the Netherlands challenging the fixed UFR.Choice of UFR – lessons from history

Surprisingly there has been little debate over the fixed 4.2% UFR despite this effectively being a “collective bet on long-term economics”. CEIOPS derived 4.2% from the sum of a long-term expected inflation rate of 2% and expected short-term return on risk-free bonds of 2.2%. It is questionable whether this choice of UFR is sustainable. CEIOPS based its assumptions on the previous 15-20 years of inflation targeting by central banks, rather than the high inflation rates of much of the 20th Century. But can we rule out further fundamental changes to monetary policy in the next 15-20 years?1st lesson from history: USA 1994

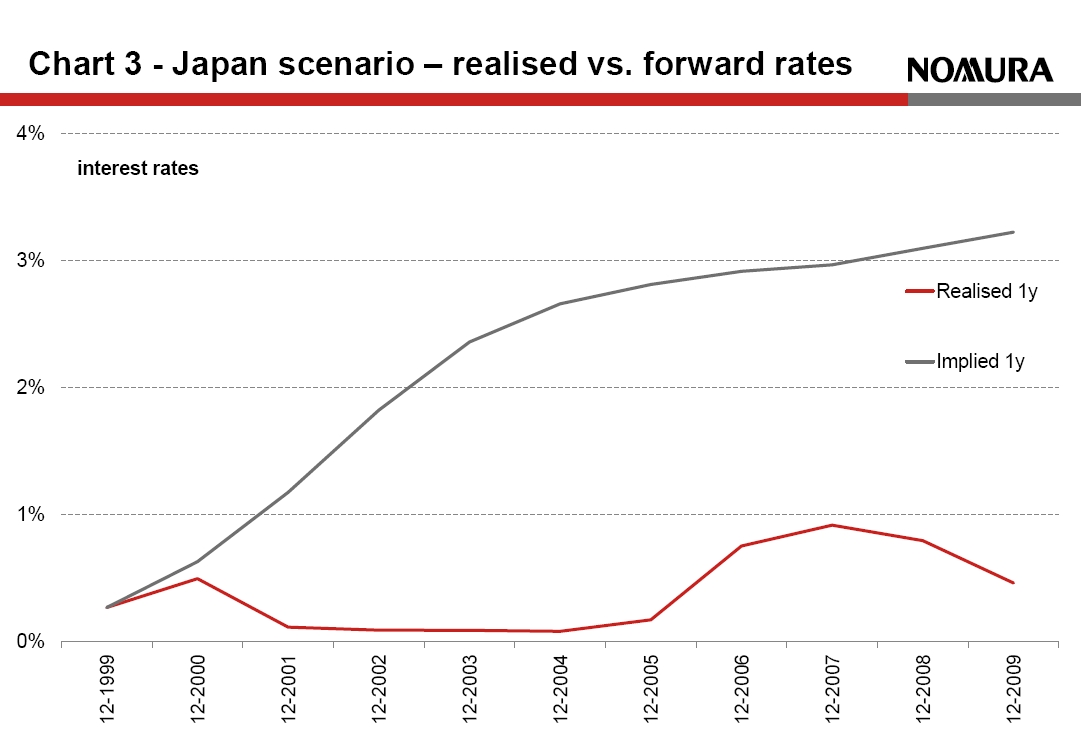

Testing the proposed Solvency II Extrapolation against historical scenarios demonstrates how exposed it can leave insurers. In the USA we saw a scenario of a sudden rise in rates caused by even small changes to monetary policy in 1994 when, following a prolonged rate cutting cycle, the Fed implemented a surprise 25 basis point rate hike. This was intended to signal its determination to control inflation and anchor long-end rates. Unfortunately the rate hike had the opposite effect, causing long-end rates to rise by 200-300bps in the US, Europe and the UK. [caption id="attachment_119111" align="alignright" width="233"] Chart 3 Japan scenario – realised vs forward rates[/caption]

In such a scenario, the 4.2% UFR would become overly-prudent. It is unlikely regulators would react quickly enough to prevent insurers’ regulatory solvency falling below market consistent levels, with losses afflicting insurers who had prudently hedged on an economic basis.

Chart 3 Japan scenario – realised vs forward rates[/caption]

In such a scenario, the 4.2% UFR would become overly-prudent. It is unlikely regulators would react quickly enough to prevent insurers’ regulatory solvency falling below market consistent levels, with losses afflicting insurers who had prudently hedged on an economic basis.

2nd lesson from history: Japan

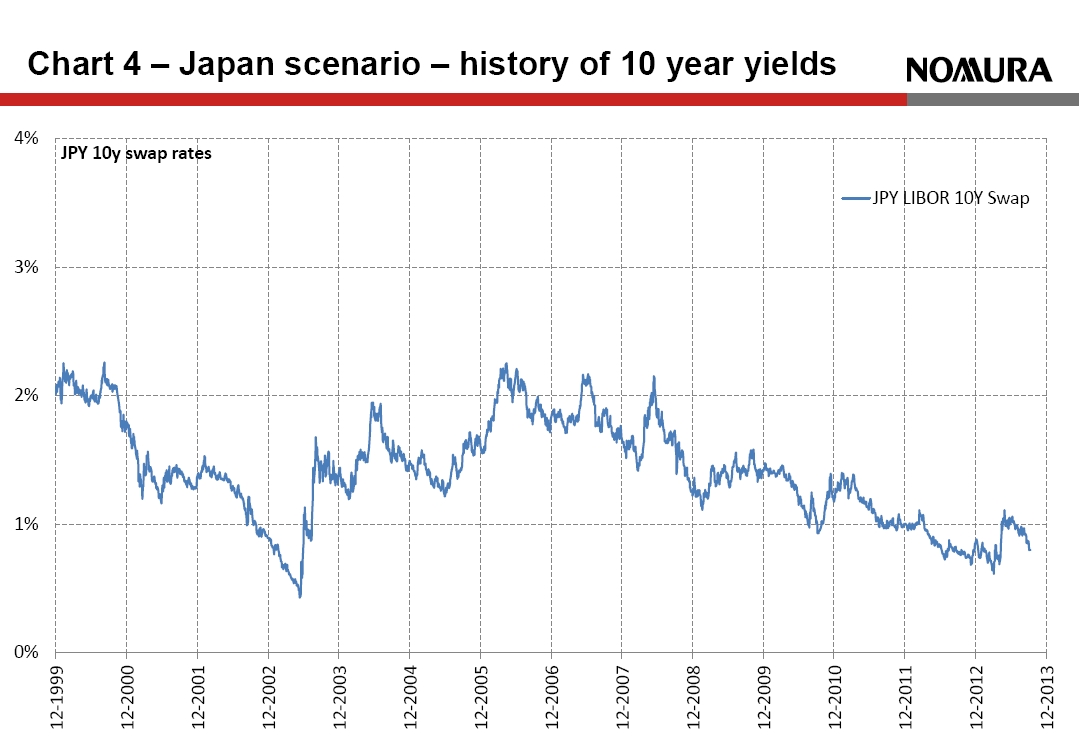

The chosen UFR is deliberately higher than current market rates, but this bases regulation on the implicit assumption that current yields are artificially low and actual realised forward rates will exceed market rates. The lesson from the Japanese scenario is that this may be a dangerous assumption. [caption id="attachment_119112" align="alignright" width="233"] Chart 4 Japan scenario – history of 10 year yields[/caption]

The interest rate curve of the Japanese Yen at the end of 1999 was remarkably similar to that of EUR today. Rates seemed very low but what we have learned is that in a balance-sheet recession – such as the one Europe is experiencing – rates can remain low for longer than expected. In practice, realised rates in Japan were consistently well below market forward rates, which led to solvency problems for insurers – see Chart 3.

In a Japan-style environment, the regulator would likely decide that the 4.2% UFR is unsustainable. Indeed the original CEIOPS proposal was to apply a 3.2% UFR in Japan and Switzerland for this very reason, suggesting that they recognised that a one-sized-fits-everywhere-for-all-time fixed UFR will not, in practice, be sustainable. Such a one-off adjustment to the UFR at some point in the future may prove a painful shock to insurers’ capital.

An even more worrying lesson from the Japanese experience is that the two scenarios aren’t mutually exclusive. As shown in Chart 4, a sharp rate sell-off in 2003 proved to be a temporary interruption in the trend to ever lower rates.

Chart 4 Japan scenario – history of 10 year yields[/caption]

The interest rate curve of the Japanese Yen at the end of 1999 was remarkably similar to that of EUR today. Rates seemed very low but what we have learned is that in a balance-sheet recession – such as the one Europe is experiencing – rates can remain low for longer than expected. In practice, realised rates in Japan were consistently well below market forward rates, which led to solvency problems for insurers – see Chart 3.

In a Japan-style environment, the regulator would likely decide that the 4.2% UFR is unsustainable. Indeed the original CEIOPS proposal was to apply a 3.2% UFR in Japan and Switzerland for this very reason, suggesting that they recognised that a one-sized-fits-everywhere-for-all-time fixed UFR will not, in practice, be sustainable. Such a one-off adjustment to the UFR at some point in the future may prove a painful shock to insurers’ capital.

An even more worrying lesson from the Japanese experience is that the two scenarios aren’t mutually exclusive. As shown in Chart 4, a sharp rate sell-off in 2003 proved to be a temporary interruption in the trend to ever lower rates.